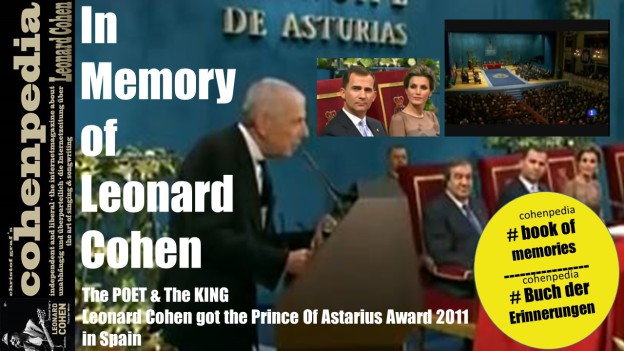

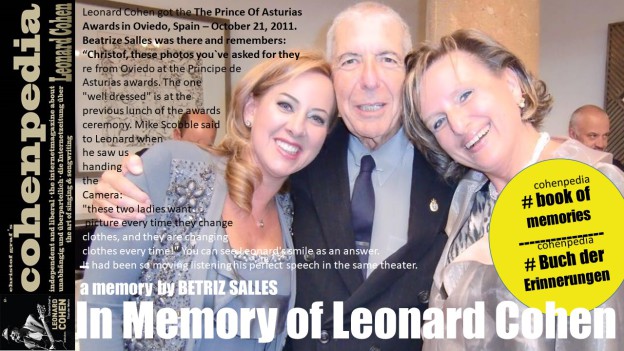

Prince Of Asturias Award –> Auszeichnungen à Dieser Preis wird seit 1981 von der Stiftung Prinz von Asturien jährlich in Oviedo, der Hauptstadt des Fürstentums Asturien, in Anwesenheit des spanischen Thronfolgers Infant Felipe von Spanien (und seit 2004 seiner Gemahlin Doña Letizia) vergeben. Die Veranstaltung kommt einer Art Verleihung eines akademischen Grades nahe. Jury und Preisträger gehören zur intellektuellen Schicht. Die Preisträger, die von der meist hochkarätigen Jury gekürt werden, zeichnen sich durch besondere Fähigkeiten und Leistungen aus. Acht Kategorien werden hierbei berücksichtigt: Kunst, Literatur, Sozialwissenschaften, Kommunikation und Geisteswissenschaften, Eintracht, internationale Zusammenarbeit, wissenschaftliche und technische Forschung und Sport. Cohen erhielt ihn am 23. Oktober 2011 in der Kategorie „Geisteswissenschaft und Literatur“. Er wurde ihm wie gewöhnlich im Theater Campoamor überreicht. Der Prinz-von-Asturien-Preis ist mit einem Geldbetrag in Höhe von 50.000 Euro dotiert. Darüber hinaus erhielt Leonard Cohen wie jeder Preisträger eine Skulptur, die vom katalanischen Künstler Joan Miró entworfen wurde.

Prince Of Asturias Award –> Auszeichnungen à Dieser Preis wird seit 1981 von der Stiftung Prinz von Asturien jährlich in Oviedo, der Hauptstadt des Fürstentums Asturien, in Anwesenheit des spanischen Thronfolgers Infant Felipe von Spanien (und seit 2004 seiner Gemahlin Doña Letizia) vergeben. Die Veranstaltung kommt einer Art Verleihung eines akademischen Grades nahe. Jury und Preisträger gehören zur intellektuellen Schicht. Die Preisträger, die von der meist hochkarätigen Jury gekürt werden, zeichnen sich durch besondere Fähigkeiten und Leistungen aus. Acht Kategorien werden hierbei berücksichtigt: Kunst, Literatur, Sozialwissenschaften, Kommunikation und Geisteswissenschaften, Eintracht, internationale Zusammenarbeit, wissenschaftliche und technische Forschung und Sport. Cohen erhielt ihn am 23. Oktober 2011 in der Kategorie „Geisteswissenschaft und Literatur“. Er wurde ihm wie gewöhnlich im Theater Campoamor überreicht. Der Prinz-von-Asturien-Preis ist mit einem Geldbetrag in Höhe von 50.000 Euro dotiert. Darüber hinaus erhielt Leonard Cohen wie jeder Preisträger eine Skulptur, die vom katalanischen Künstler Joan Miró entworfen wurde.

Leonard Cohen hielt bei der Verleihung eine eindringliche Rede mit dem Titel: „How I Got This Song“, die auf YOUTUBE nachzuhören ist.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-27-q7biKs

Quelle: ZEN & POESIE – Cohenpedia Series Vol. 1

Die Prinz-von-Asturien-Preise (span.: Premios Príncipe de Asturias) wurden 1981 erstmals durch

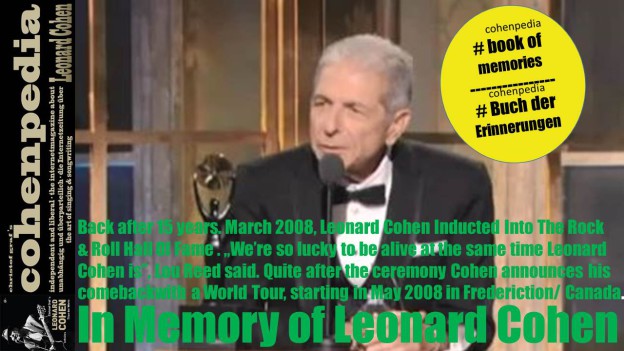

Dieser Preis wird seit 1981 von der Stiftung Prinz von Asturien vergeben. Zum ersten Mal vom spanischen Pinzen 1981 und dann jährlich in Oviedo, der Hauptstadt des Fürstentums Asturien wird er in Anwesenheit des spanischen Thronfolgers Infant Felipe von Spanien (und seit 2004 seiner Gemahlin Doña Letizia) vergeben.

Die Preisverleihung kommt einer Art Verleihung eines akademischen Grades nahe. Jury und Preisträger gehören zur Intellektuellen Schicht. Die Preisträger, die von der meist hochkarätigen Besetzung gekürt werden, zeichnen sich durch besondere Fähigkeiten nund Leistungen aus. Acht Kategorien werden hierbei berücksichtigt: Kunst, Literatur, Sozialwissenschaften, Kommunikation und Geisteswissenschaften, Eintracht, internationale Zusammenarbeit, wissenschaftliche und technische Forschung und Sport. Cohen erhielt ihn in der Kategorie „Geisteswissenschaft und Literatur“.

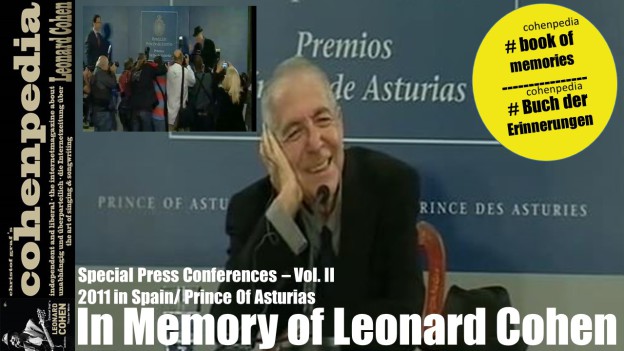

Am 23. Oktober 2011 erhielt Leonard Cohen diese Auszeichnung: Der Preis wurde wie gewöhnlich im Theater Campoamor überreicht. Der Prinz-von-Asturien-Preis ist mit einem Geldbetrag in Höhe von 50.000 Euro dotiert. Darüber hinaus erhielt Leonard Cohen wie jeder Preisträger eine Skulptur, die vom katalanischen Künstler Joan Miró entworfen wurde, überreicht.

Leonard Cohen hielt bei der Verleihung eine eindringliche Rede mit dem Titel: „How I Got This Song“, die auf YOUTUBE nachzuhören ist. Anbei das Transkript:

It is a great honour to stand here before you tonight. Perhaps, like the great maestro, Riccardo Muti, I’m not used to standing in front of an audience without an orchestra behind me, but I will do my best as a solo artist tonight.

I stayed up all night last night wondering what I might say to this assembly. After I had eaten all the chocolate bars and peanuts from the minibar, I scribbled a few words. I don’t think I have to refer to them. Obviously, I’m deeply touched to be recognized by the Foundation. But I have come here tonight to express another dimension of gratitude; I think I can do it in three or four minutes.

When I was packing in Los Angeles, I had a sense of unease because I’ve always felt some ambiguity about an award for poetry. Poetry comes from a place that no one commands, that no one conquers. So I feel somewhat like a charlatan to accept an award for an activity which I do not command. In other words, if I knew where the good songs came from I would go there more often.

I was compelled in the midst of that ordeal of packing to go and open my guitar. I have a Conde guitar, which was made in Spain in the great workshop at number 7 Gravina Street. I pick up an instrument I acquired over 40 years ago. I took it out of the case, I lifted it, and it seemed to be filled with helium it was so light. And I brought it to my face and I put my face close to the beautifully designed rosette, and I inhaled the fragrance of the living wood. We know that wood never dies. I inhaled the fragrance of the cedar as fresh as the first day that I acquired the guitar. And a voice seemed to say to me, “You are an old man and you have not said thank you, you have not brought your gratitude back to the soil from which this fragrance arose. And so I come here tonight to thank the soil and the soul of this land that has given me so much.

Because I know that just as an identity card is not a man, a credit rating is not a country.

Now, you know of my deep association and confraternity with the poet Frederico Garcia Lorca. I could say that when I was a young man, an adolescent, and I hungered for a voice, I studied the English poets and I knew their work well, and I copied their styles, but I could not find a voice. It was only when I read, even in translation, the works of Lorca that I understood that there was a voice. It is not that I copied his voice; I would not dare. But he gave me permission to find a voice, to locate a voice, that is to locate a self, a self that that is not fixed, a self that struggles for its own existence.

As I grew older, I understood that instructions came with this voice. What were these instructions? The instructions were never to lament casually. And if one is to express the great inevitable defeat that awaits us all, it must be done within the strict confines of dignity and beauty.

And so I had a voice, but I did not have an instrument. I did not have a song.

And now I’m going to tell you very briefly a story of how I got my song.

Because – I was an indifferent guitar player. I banged the chords. I only knew a few of them. I sat around with my college friends, drinking and singing the folk songs and the popular songs of the day, but I never in a thousand years thought of myself as a musician or as a singer.

One day in the early sixties, I was visiting my mother’s house in Montreal. Her house was beside a park and in the park was a tennis court where many people come to watch the beautiful young tennis players enjoy their sport. I wandered back to this park which I’d known since my childhood, and there was a young man playing a guitar. He was playing a flamenco guitar, and he was surrounded by two or three girls and boys who were listening to him. I loved the way he played. There was something about the way he played that captured me. It was the way that I wanted to play and knew that I would never be able to play.

And, I sat there with the other listeners for a few moments and when there was a silence, an appropriate silence, I asked him if he would give me guitar lessons. He was a young man from Spain, and we could only communicate in my broken French and his broken French. He didn’t speak English. And he agreed to give me guitar lessons. I pointed to my mother’s house which you could see from the tennis court, and we made an appointment and settled a price.

He came to my mother’s house the next day and he said, “Let me hear you play something.” I tried to play something, and he said, “You don’t know how to play, do you?’

I said, “No, I don’t know how to play.” He said “First of all, let me tune your guitar. It’s all out of tune.” So he took the guitar, and he tuned it. He said, “It’s not a bad guitar.” It wasn’t the Conde, but it wasn’t a bad guitar. So, he handed it back to me. He said, “Now play.”

I couldn’t play any better.

He said “Let me show you some chords.” And he took the guitar, and he produced a sound from that guitar I had never heard. And he played a sequence of chords with a tremolo, and he said, “Now you do it.” I said, “It’s out of the question. I can’t possibly do it.” He said, “Let me put your fingers on the frets,” and he put my fingers on the frets. And he said, “Now, now play.”

It was a mess. He said, ” I’ll come back tomorrow.”

He came back tomorrow, he put my hands on the guitar, he placed it on my lap in the way that was appropriate, and I began again with those six chords – a six chord progression. Many, many flamenco songs are based on them.

I was a little better that day. The third day – improved, somewhat improved. But I knew the chords now. And, I knew that although I couldn’t coordinate my fingers with my thumb to produce the correct tremolo pattern, I knew the chords; I knew them very, very well.

The next day, he didn’t come. He didn’t come. I had the number of his, of his boarding house in Montreal. I phoned to find out why he had missed the appointment, and they told me that he had taken his life. That he committed suicide.

I knew nothing about the man. I did not know what part of Spain he came from. I did not know why he came to Montreal. I did not know why he played there. I did not know why he he appeared there at that tennis court. I did not know why he took his life.

I was deeply saddened, of course. But now I disclose something that I’ve never spoken in public. It was those six chords, it was that guitar pattern that has been the basis of all my songs and all my music. So, now you will begin to understand the dimensions of the gratitude I have for this country.

Everything that you have found favourable in my work comes from this place. Everything , everything that you have found favourable in my songs and my poetry are inspired by this soil.

So, I thank you so much for the warm hospitality that you have shown my work because it is really yours, and you have allowed me to affix my signature to the bottom of the page.